Singing and travel go together. Whether we are merrily rowing along, going home on country roads, or leaving on a jet plane, something about going places brings the melodies out of us. Maybe it’s the lure of the adventure or the destination; maybe it’s the delight of travel companions; maybe it’s the freedom from firm footing. I suspect people have been singing as they travel for as long as people have been singing…and traveling. It’s an ideal way to pass the time, stay awake, and scare away wildlife.

Sometimes our travel songs are ninety-nine bottles of nonsense. But sometimes they mean something—like the quiet worship songs my youth group sang in the back of the bus as the night wore on. And other times our songs achieve something, too—like the hymns I sing to keep anxiety at bay when I’m traveling alone.

Many scholars think the Psalms of Ascent were travel songs, of a sort—and as such, they both meant and achieved something. They expressed the beliefs and hopes of the community, and they bound the people together in shared experience.

Each psalm in the Psalms of Ascent begins with the title, or superscription, “A song of ascents” (“degrees,” in the King James).1 This superscription tells us something about the songs—though we’re not exactly sure what it tells us.2 The word ascents (Hebrew ma‘aloth) is used for steps or stairs that went up to the altar, the king’s throne, the palace, the temple, and the City of David. The related verb is used to refer to the “going up” or “ascending” to the land of Israel. So, something or someone is going up somewhere. Helpful, right?

Of the many suggestions for what’s ascending in the songs of ascent, three seem most plausible.

1. Israelite pilgrims going up to the Jerusalem temple. Jerusalem is only 2,500 feet above sea level, so we’re not talking about Mount Everest. However, it’s tucked between the Dead Sea (1415 below sea level) to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west—so, yeah, you’ll break a sweat walking those hills.

Three times a year (as life allowed), Israelites traveled to Jerusalem for special festivals: (1) in the spring for Passover; (2) seven weeks later to mark the wheat harvest (Festival of Weeks/Pentecost); (3) in the fall for the Festival of Tabernacles, an annual commemoration of the wilderness wandering. The songs frequently mention Jerusalem/Zion and the temple, so there’s decent merit to the suggestion that “going up” pilgrims sang these songs as they went.

2. Diaspora Jews longing to go up to a restored Jerusalem to worship. Diaspora refers to Israel’s history beginning in 587 BC when the Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem and took the people into exile. The Diaspora actually continues to this day; there are countless Jews living outside the land of Israel, “scattered among the nations,” in the language of the Old Testament.

The Diaspora represents a time of wandering without a permanent home and longing for the day when all will be restored and made right again. The songs of ascent talk about the return from exile and about foreign people, so it’s plausible that those waiting and hoping for the day they could worship in the Jerusalem temple again sang these songs.

They are the songs of God’s people living in a world that isn’t the way it was meant to be. They are people journeying to a world where all has been made right, where God reigns unopposed.

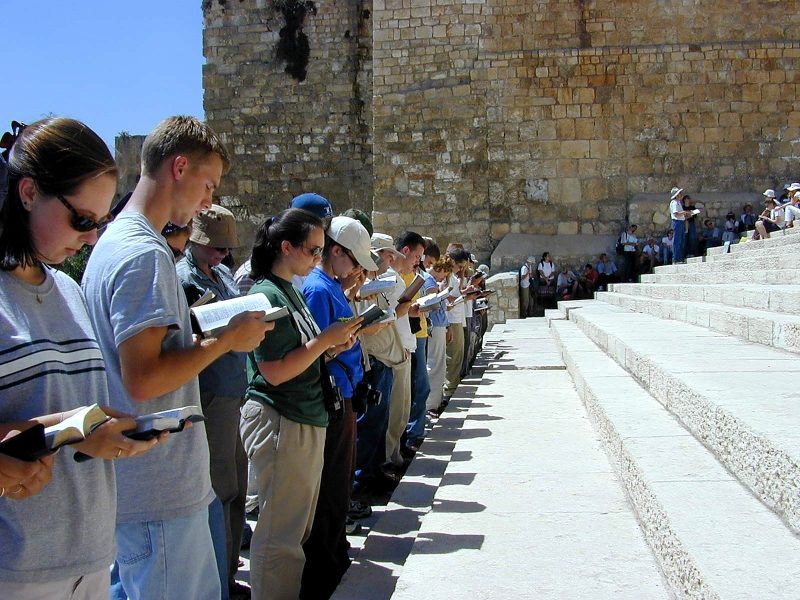

3. The steps going up to the temple complex. On the southern end of the Temple Mount, a magnificent staircase led to the temple gates. Excavated in the late 1960s, the thirty steps spanned 200 feet steps. Fifteen of the steps are deeper than the rest, and some people think that when the pilgrims arrived at the temple, they paused on these steps to sing the songs of ascents as they went up to the temple gates.

Exactly which of these three possibilities is correct is impossible to know. But I don’t think we have to choose. That’s one of the beautiful things about the Psalms. Most of them are not context specific—so, while we can (and should) think about why the original audience would have sung them, we can’t really know. This is what gives the Psalms their wonderfully transcendent character, their ability to speak across time and space. They take us to the depths of human emotion—which hasn’t changed over time. We understand these songwriters. We may not live in their time and place, but nonetheless, we live in their world.

For whatever else these “Pilgrim Psalms” may have been used, it is clear that they are the songs of God’s people living in a world that isn’t the way it was meant to be. They are people journeying to a world where all has been made right, where God reigns unopposed.

And really, that’s us. We are still God’s people, living in a world that isn’t the way it was meant to be. We are pilgrims journeying to the new earth where all will be made right again. These songs are for us.

——————-

1 Yes, the plural “ascents” is correct, but for reasons I can’t explain, the title of the entire collection is typically given in the singular, the Psalms of Ascent.

2 Superscriptions appear on many psalms, though we usually read right past them. In English Bibles, they are typically italicized and centered below the chapter/psalm heading, but in Hebrew Bibles, the superscriptions make up much of the psalm’s first verse.

Many of these titles relate to David (“A psalm of David”), while some mention other people, known and unknown—such as Asaph, Moses, and an Ethan the Ezrahite. Some titles include musical directions that don’t mean much to us but must have been important for performance, such as “For the director of music. To the tune of ‘Lilies.’” The superscriptions we tend to notice say something about the circumstances behind the composition—like the one that heads Psalm 51: “For the director of music. A psalm of David. When Nathan the prophet came to him after David had gone in to Bathsheba.”

* The picture is a group of pilgrims/tourists reading the Psalms of Ascent as they go up the excavated southern steps of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. (Pictorial Library of Bible Lands, vol. 3).

Recent Comments